Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton (1716 –1799) was a French

naturalist who assisted George-Louis Leclerc de Buffon with Buffon’s

famous natural history work, the Histoire Naturelle, Générale et

Particulière. He also was instrumental in the importation of Merino

sheep into France, where they became the basis for the Rambouillet

breed. Daubenton lectured on natural history in the College of

Medicine and on rural economy at the Alfort school. In 1782 he

published Instruction pour les Bergers et les Propriétaires de

Troupeaux, which appeared in an English translation in 1811 as

Advice to Shepherds and Owners of Flocks on the Care and Management

of Sheep. The book is in the form of a series of questions and

answers. Among the topics he covered were the qualifications needed

by a good shepherd and the handling and training of shepherds’ dogs.

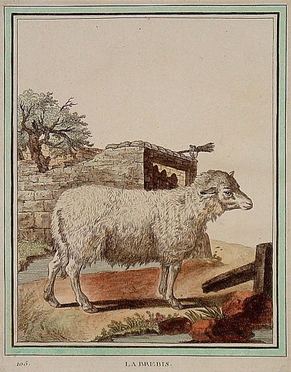

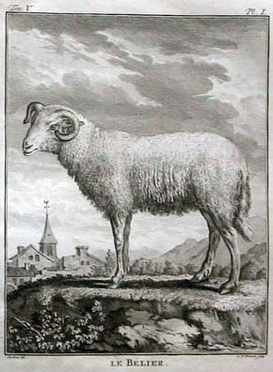

From Buffon’s Natural History, 18th century:

The shepherd's dog

from INSTRUCTION POUR LES BERGERS (Advice for Shepherds)

by Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton

CHAPTER I.

ON THE QUALIFICATIONS OF A SHEPHERD.

Question.

What should be the age of a shepherd to take charge of a flock of

sheep?

Answer.

His age is of no importance, if he is strong enough to carry the

hurdles for the pen, and considerate enough to mind his business,

instead of playing with his comrades.

Q.

Will the business of

a shepherd employ a man his whole time, and enable him to obtain an

honest livelihood?

A

A careful and well informed shepherd, who has the care of a large

flock, is almost continually employed in conducting it properly

during the day, in folding it for the night, in feeding it in bad

weather, in keeping it clean, in treating its diseases, &c.

Shepherds receive good wages and are well paid in countries, where

sheep are maintained, that is, when they know their business, and

will carefully perform it.

Q. Are

many qualifications necessary to become a good shepherd?

A. More

things are necessary to be known in the business of a shepherd than

in most other agricultural employments. A good shepherd should

understand the best method of folding, feeding, watering, and

pasturing his flock, of treating its diseases, and improving it, as

well in the breed, as in the quality and fineness of the wool; to

drive, wash, and shear his flock in the best manner; to rear and

train dogs, and keep them in subjection, and to protect the flock

against wolves, and other noxious animals.

Q. How

can it be known that a young man will make a good shepherd?

A. A good

shepherd may be expected from one who understands and retains what

is told him as well as other young men in the country; if he is

careful and patient, and has no infirmity, which will hinder him

from walking or standing for a length of time together.

Q. Is it

necessary that a shepherd should know how to read?

A. One, who understands reading, more readily acquires information, but it

is not absolutely necessary; he however, would be the more valuable

for knowing how to read, write, and cypher.

Q. With

what necessaries should a shepherd be provided to manage his flock

in the fields?

A. He

should be well clothed, so as to continue the whole day in the

field, without suffering much from cold, or from being exposed for a

long time in the rain, without being wet to the skin. He should have

a crook, a whip, a scratcher, a knife, a lancet, a tin box prepared

with a suitable ointment, and a scrip.

. . .

Q. What

is a crook, and for what purpose is it used?

A. The

crook is a staff about six feet long, terminated on the upper end by

an iron, which is in the form of a small spade, and on the other end

by a hook bent back on the top; the hook may be put on the side of

the flat iron, and then it should be bent inward. The flat iron of

the crook is intended to throw earth near the sheep, which stray

from the flock, so as to make them return. The hook is made for

seizing and catching them by one of the hind legs.

Q. What

is a shepherd's scrip, and for what purpose is it used?

A. A

scrip is a pocket or knapsack, attached to a leather string, which

the shepherd carries like a shoulder belt. He puts, in his scrip,

his provisions for the day, a box of ointment to rub such sheep as

he sees scratching themselves in the field; a scratcher to remove

the scabs of the itch before applying the ointment; a lancet to

bleed such sheep as may require it; a small knife to skin, and to

open such as may die in the field, &c.

Q. Is it

necessary to have a scratcher, knife, and lancet in separate

instruments?

A. A

single instrument is sufficient, that is, a small knife, which shuts

on its handle, the end of the handle being flattened and brought to

an edge, makes a scratcher; the blade, being pointed, and sharp on

both sides, near the point, serves as a lancet.

CHAPTER II.

OF DOGS AND WOLVES.

Q. Is it

necessary, that shepherds should have dogs for driving their flocks?

A. It is

to be wished, that shepherds could dispense with them, because they

often do much mischief; but they are necessary in countries, where

the lands are often sown with corn, and exposed to injury: when

sheep stray from the flock, the shepherd can restrain those only,

which are near him, and at the distance, at which, he can throw

lumps of earth before them with his crook : dogs, therefore, assist

the shepherd in driving his flock, and defend it against wolves,

when strong enough.

Q. In

what countries can a shepherd manage his flock without the aid of

dogs?

A. In

places, where the land is divided into large enclosures, there is

always a great deal of ground in fallow, that is, not sown; a

numerous flock can be there conducted without the aid of dogs. Sheep

naturally go together; they do not stray from the flock, except they

observe a better pasture, than where they are; this allurement is

commonly too far from great fallows, to attract them; but if the

flock should be on one end of a fallow, near land liable to injury,

the shepherd places himself on the side of such lands, to protect

them.

Q. What

injury can dogs do sheep, and how can they be restrained?

A. Dogs

badly disciplined, and too ardent, fly upon the sheep, bite and

wound them, and cause abscesses. They frighten the ewes with young,

by hurting them, and making them miscarry. They throw down the weak,

and such as can hardly follow the flock, or fatigue and fret them,

by driving them too fast. To prevent these inconveniences, it is

proper to make use of such dogs only in driving as are mild and good

natured, and well trained to shew their teeth to wolves, but not to

sheep. A good well-bred dog makes them obey without hurting them.

Sheep are accustomed to do of themselves, what the dog would compel

them to, by force. They withdraw when he approaches, and do not

advance on the side, where they see him a sentinel, on the borders

of a prohibited ground.

Q. How do

dogs serve to direct the course of a flock?

A. When a

shepherd drives his flock before him, he can greatly hasten its

speed, and that of the sheep, which remain behind ; but he cannot

prevent it from going too quick, nor the sheep from running forward

too fast, or straying to the right or left; it is necessary, he

should have the aid of dogs, to place round the flock, to send

forward, or to restrain such as go too fast, to bring up those which

remain behind, or stray to the right or left.

Q. How

can a shepherd make his dog perform these different manoeuvres?

A. He

must train them from their youth, and accustom them to obey his

voice. The dog goes on all sides; before the flock to stop it;

behind it, to make it go forward; on the sides, to prevent it from

straying: he remains at his post, or returns to the shepherd,

according to signs given him, which he understands.

Q. What

is necessary to be done to train a shepherd's dog?

A. He must be learnt to stop, to lie down, to bark, to stop barking, to

place himself on the side of the flock, to walk round it, and to

seize a sheep by the ear, at the command of the shepherd, when given

him by the sound of his voice, or by the motion of his hand.

Q. How is

a dog taught to stop, or lie down, at command?

A. By

pronouncing the word

stop, a piece of bread

or other food should be given him, which makes him stop, or he is

stopped by force; by repeating this manoeuvre, he is accustomed to

stop, at the sound of the voice. To teach him to lie down, when

required, it is necessary to caress him, when he does it of himself; or after having obliged him to it, by taking him by the legs and

pronouncing the words lie down; if he would rise too soon, he is

chastised, to make him remain. When he is quiet, they give him

something to eat, and by these means he is made to obey.

Q. How do

they make a dog bark, or stop barking, at command?

A. The

barking of the dog is to be imitated, while he is shown a piece of

bread, which is given him, as soon as he has barked, when the word

bark is repeated: he

is accustomed also to stop barking, when the world

silence is pronounced: he is threatened or

chastised, when he does not obey, and rewarded and caressed,

when he does.

Ewe and ram from Buffon’s

Natural History, 18th Century

Q. At

what age is it proper to train dogs for the use of a shepherd?

A. They

begin training them when six months old, if they have been well fed,

and are strong; but if they are weak, it is necessary to wait, until

they are nine months old.

Q. How is

a dog made to go round a flock, to pass on its side, to run before,

to come back, or to remain in his place?

A. To

learn a dog to go round, a stone must be thrown before him, and then

successively from place to place, until he shall have gone round the

flock, always repeating the word turn, by throwing a stone before, and then

behind him; he is trained to run on the side of a flock, by

pronouncing the words, on the sides; they say, go, to make him go before; return,

to make him return; stop,

to continue in place; other words may be substituted, in places here shepherds have another language.

Q. How is

a dog learnt to seize a sheep by the ear to bring him back when he

wanders, or to stop him in the middle of the flock, to wait for the

shepherd?

A. A dog

is made to go round a single sheep in an enclosure: the ear of the

sheep is put to the dog's mouth, to accustom him to seize the sheep

thereby: or a piece of bread is tied to the ear of a sheep in the

middle of a flock, when the dog is excited to aim thereat, and is

thus habituated to seize the ear. In this manner a dog is taught to

stop such sheep as the shepherd may shew him in the flock. Dogs may

also be taught to stop sheep, by seizing them by the leg, before or

behind, or above the fetlock: but this practice has its

inconveniencies; the fetlock is often swelled by it, and the sheep

made lame for some time.

Q. How

does a dog make a flock obey him?

A. He makes the first sheep fly before him, by running at him, and then

one after the other, the whole flock takes the same course, if the

dog continues to press forward: when a sheep is not ready enough to

obey him, he approaches and threatens him by barking.

Q. When a

dog is well trained, can he instruct another?

A. It

requires less time and trouble to teach a young dog, when he has the

example of one, which knows how to drive the flock: the young dog

will take the same gait, but he is often deceived; he would,

perhaps, be never well taught, if the shepherd did not learn him

such things, as the example of the other dog could not make him

understand.

Q. What

kind of dogs, and how many, are proper for the service of flocks?

A. All

active docile dogs are good for training to the service; those are

called dogs of the true breed, whose fathers and mothers are well

practised in conducting flocks; it is thought, that dogs, thus bred,

are more easily trained, than others. In parts of the country, where

the lands are rarely exposed to be injured by sheep, a single dog is

sufficient for an hundred sheep; but when they are so exposed, and

are near to sheep walks, which the flock often approaches, two, and

even three and four dogs are necessary; because two could not stand

for the whole day, or for many successive days, the almost continual

running, which they are obliged to make, to keep the sheep from the

prohibited lands; it would therefore be necessary to have other dogs

to relieve, and to give them rest, when much fatigued. In countries

where wolves are to be apprehended, it is necessary, that the dogs

should be strong enough to resist, and bold enough to hunt them.

Dogs well covered with hair, support cold and rain better than

others.

Q. What

breed of dogs is preferred, in countries where wolves are little to

be dreaded.

A. A

breed of dogs called shepherds’ dogs, from being commonly used in

the service of flocks; they are naturally active, and easily made

docile: dogs of every other breed may be trained for the same

purpose.

Q. What

is the best breed of dogs for guarding sheep, where wolves are to be

apprehended?

A. The

mastiff breed is best: these dogs are strong and courageous; but it

is necessary to give them collars armed with long iron points; and

to incite them against the wolf, the first time they have to fight

him, or to put them in company with other dogs trained to the

business.

Q. What

precautions are necessary, when you have a badly disciplined dog,

that wounds the sheep?

A. The

long canine teeth, which enter deep into the flesh, should be broken

off, in case he bites.

Q. How

ought shepherds’ dogs to be fed?

A. It

costs but little to feed them, in the neighbourhood of large cities,

where horse-meat, the scraps of tallow, &c. can be easily procured;

for the want thereof, coarse bread must be made for them: it is

improper to give them mutton; because, if they are accustomed to

this feed, they will acquire the habit of biting the sheep, for the

sake of the blood. Mastiffs are trained, like other dogs to driving

sheep.

Q. Have

not shepherds some means of driving their flocks when they have no

dogs?

A.

Shepherds teach some sheep of the flock, to which they give

particular names, to come to them, at their call; and in order that

they may take this habit, they are enticed to follow them by giving

them pieces of bread. When the shepherd would make the flock pass a

narrow path, or passage-way, on its route, or would collect his

flock, he makes the tame sheep come to him; such as are near

accompany them, others take the same course, and immediately the

whole flock becomes disposed to follow the shepherd.

Q. What

precautions should a shepherd take against wolves?

A. 1st.

He should tie small bells to the necks of a certain number of sheep,

which have strayed into the woods, and other places out of his

sight. When a wolf approaches, the sheep are commonly the first to

discover him; they are frightened an agitated in a manner, to make

their bells heard, which disclose their danger, both to the dogs an

shepherd. The little bells also call the shepherd, when something

extraordinary happens in the flock, whether by night or by day,

which puts the sheep in motion.—2nd. The shepherd takes care that

his flock be accompanied by dogs strong and courageous enough to

face a wolf, to put him to flight, to pursue, and even to kill

him.—3rd. The shepherd carefully observes his flock, when it drives

it near woods, or places frequented by wolves. The same attention

should be paid when he is near fields, where the grass or growth is

high enough to conceal them; they are always to be feared in foggy

weather, and in the dusk of the evening, and above all, near hedges

and bushes, where they keep themselves in ambush.— 4th. Shepherds

also make fires, or at least smoke, near their flocks.

Q. What

ought the shepherd to do, when wolves approach the flock, or have

seized upon some of the sheep?

A. When

the wolf appears, the shepherd collects his flock, and sends his

dogs in pursuit of him; he remains near the flock, to observe if he

can see other wolves; halloos to the wolf, and encourages his dogs.

But if the wolf has already seized his prey, the shepherd runs after

him, without, however, losing sight of the flock, urges the dogs to

the battle, and forces him to abandon his prey, which often happens.

. . .

Merino sheep with a goat;

from a 19th century edition of Buffon’s Natural History

CHAPTER V.

CONCERNING THE MANAGEMENT OF SHEEP IN PASTURES.

Q. What

are the principal rules which shepherds should observe, in grazing

their flocks?

A. They may be reduced to seven.

1st. To graze them every day, if possible.

2d. Not to stop them too often while grazing, except

in closed pastures.

3d. To prevent them from doing damage, when grazing

on lands liable to injury.

4th. To avoid moist soils, and grass covered with

dew or white frost

5th. To put the flock in the shade, during the sun's

greatest heat; and to drive it in the morning as much as possible,

on the side lands, exposed to the west, and in the evening, to such as

present to the east.

6th. To remove the flock from grasses, which may

prove hurtful to them.

7th. And to drive it slowly, particularly when

ascending hills.

Q. Why

should sheep be made to graze every day?

A.

Because it is the most natural, and least costly manner of feeding

them; and which can be but imperfectly done, by giving them fodder at the rack. In grazing, they have a choice

of food, and take it in the best state; grass is always much better

for them, than hay or straw. Even if food could not be found in the field,

the exercise they would receive in walking, would give them an

appetite for their fodder.

Q. Why

are sheep allowed to wander, while pasturing?

A. Because it would disturb, to stop them when grazing: it is

their natural disposition, in seeking their food to wander from

place to place; this exercise preserves their vigour.

Q. Why

are not sheep allowed to graze in enclosed pastures, as in open

fields ?

A.

Because sheep, when allowed to run over a rich pasture, spoil more

grass with their feet than they eat. To preserve the feed, the flock

should be allowed every day, only such part of it, as it may

consume. The flock should be fenced in, by a pen, or fold, within

which, there should be grass enough for the number of sheep; the

next day the pen should be shifted, and so successively, until the

flock shall have eaten the whole pasture.

. . .

Q. Why

should a shepherd always drive his flock moderately, especially when

ascending hills?

A. Because, in driving his flock too quick, especially on ascending

ground, he would run the risk of heating many of the sheep, to the

degree of making them sick, and even destroying them.

Q. How

ought the shepherd to manage his flock, when driving it?

A. He

ought to prevent any animal from separating from the flock, by

running before, remaining behind, or straying to the right or left.

Q. How

can a shepherd do all that?

A. By the

aid of his whip, his crook, and his dogs; when he makes his flock go

before him, he drives the sheep behind, with his whip: the dog is

before, and restrains the sheep from going forward too fast: the

shepherd menaces those that stray to the right or left, to make them

return to the flock, or if he has a dog behind him, he sends him

after the sheep, which stray, to bring them back, or makes them

return, by throwing a little dirt at them, so as never to touch

their bodies, which is improper.

Q. How

does he set the flock forward again?

A. He

speaks to the dog, which is before, to let them advance, and then

drives forward the hinder sheep; he can make them go forward, or

return by speaking to them in different tones, to which he accustoms

them.

Q. Can a

shepherd conduct his flock by going before?

A. Yes,

if he has at least one dog, on which he can depend, to prevent any

part of the flock straying behind, or on the sides. The flock

follows the shepherd even better than the dog, but it is necessary

he should have regard to the sheep, behind.

Q. How

does the shepherd make the flock pass a narrow passage, or a bad

track?

A. The

shepherd causes some animals to follow him, which he has accustomed

to come to him at his call: he goes first, and calls them, in order

to induce them to follow him; the first, which pass, are followed by

the rest. If there should be no sheep in the flock, acquainted with

his call, he should present a piece of bread to such, as are most

ready to take it, and in this way, he can make the whole flock to

follow him.

Q. How

does a shepherd prevent his flock from doing damage to grounds sown

to grain?

A. When

the flock is near such grounds, he sends a dog upon the edge of the

field sown, to prevent any of the sheep from approaching it: if

there is a like field on the other side, he sends another dog, if he

has another; or goes thither himself.

Q. How

does the shepherd manage when he has no dog, and has two fields to

guard?

A. Whilst

he guards one of the fields, he speaks to the animals, which go upon

the other, to make them quit it; if they do not obey, he should run

after them, and drive them out. But it is necessary that a shepherd

should have, at least, one dog, when he conducts a flock near

grounds sown to grain; but a dog is not so necessary, where there

are great fallows.

Q. What

can the shepherd do, to retain his flock in a place, where the feed

is good?

A. He

induces his flock to continue, if he stays there himself with his

dogs, and plays upon some instrument, such as the flageolet, the

flute, the hautbois [oboe], or the bag-pipe, &c. Sheep are pleased

with the sound of instruments, and feed quietly, while the shepherd

is playing thereon.

The Contented Shepherd, c1660,

by David Teniers the Younger

Return of the Flock in Provence, 1882,

by Paul Vayson