|

|

|

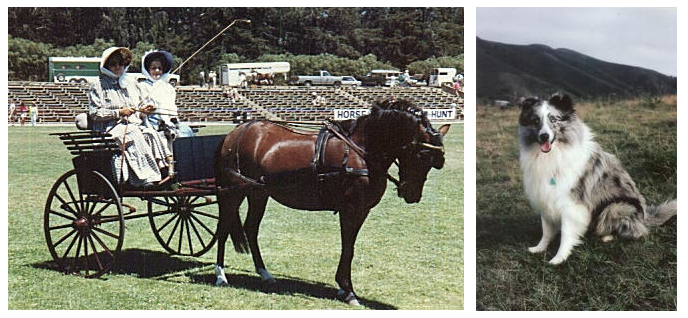

Carriage Dogs Linda Rorem I enjoy driving horse-drawn vehicles and have trained several ponies and horses to drive. Some years ago, when I still had my late Welsh Pony, Meadowlawn Penny, I thought it would be interesting and fun to train my own carriage dog. My subjects were my tricolor Rough Collie, Shasta (Paragon Wildwood Tapestry, CDX, HC) and my first Sheltie, blue merle Pascha (Glengyle Frost Bi Moonlight, UD, OTD-s, HT). In the days when highwaymen plagued the roads, dogs were trained to accompany coaches and carriages to act as watch dogs and guards. Dalmatians were popular for this work and became the fashionable breed as the work itself became more of a fashion and less of a necessity. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s classes for coach dogs were sometimes provided at horse shows. A book on Dalmatians, Dalmatian: Coach Dog - Firehouse Dog by Alfred and Esmeralda Treen (1980) has a chapter on coach dogs and references a coach dog article which appeared in the Aug. 1, 1911 issue of Country Life in America magazine, p. 52. In addition to the dogs that accompanied fancier carriages, farm dogs often accompanied the farm wagon to town, guarding the wagon and its contents. Although the Dalmatian is considered the "classic" coach or carriage dog, other breeds have also done the same kind of work, traveling with a vehicle and guarding the vehicle and its occupants and contents. In The Collie or Sheepdog (1890), Rawdon Lee writes: "The collie is admirably adapted as a companion . . . and as such he accompanies the carriage when its owner goes out for a drive; for his fondness for horses is scarcely exceeded by that of the spotted coach dog or Dalmatian."

A Morning Outing by Otto Eerelman Anecdotes of Dogs by Edward Jesse, first published in 1859 and reprinted in 1893, says of the "Great Danish Dog": ". . . like the Dalmatian, he is chiefly used in this country as an attendant on carriages, to which he forms an elegant appendage." Great Dane coach dogs, particularly those of the harlequin color, are also mentioned in the recently reprinted Classic Dog Encyclopedia by Vero Shaw, first published in 1879-81. The breed is referred to there as the "German Mastiff." Shaw quotes from an earlier work, Cynographia Britannica by Sydenham Edwards, published in 1803, where the dogs are described as often taking a position in front of the carriage. Farm dogs accompanied their master’s wagon to town to look after things or provide companionship. In the age of the automobile, Albert Payson Terhune portrayed collies guarding the open-topped cars of the 1920’s. Dogs still occasionally accompany horse drawn vehicles on pleasure drives and at shows. In book and magazine photos I have seen Dalmatians, of course, and Border Collies, German Shepherds and others following or riding along. For someone who would like to take their dog along on a drive, coaching training can be advantageous. The dog won't be darting here and there, perhaps interfering with the horse or chasing off after something. The dog should also be taught to ride quietly in the vehicle, so as not to cause problems by excessive barking or fidgeting at the approach of strange dogs or other distractions. The dog needs to be completely reliable whether coaching or riding. Carriage work or coaching isn't just tagging along. The dog should keep a particular position in relation to the vehicle at various gaits, similar to the heeling exercise in obedience competitions, should have a good stay and a recall, and continue working reliably despite distractions. There are several possibilities for the dog's position with a carriage. Nowadays it is generally just behind the carriage or even underneath up close to the axle, or at the side of the vehicle or the horse, the chosen position being used consistently. In earlier days, some drivers considered the proper place for a dog coaching to a four-wheel carriage to be under the front axle, near the horses' heels. Or the dog could travel under the rear axle. Some dogs would run along in front of the horse. Dogs have even coached under the pole between a pair of horses, or between the lead pair and wheel pair of a four-in-hand—somewhat risky locations. Methods of positioning included coupling an inexperienced dog with an experienced one, or tying the dog to the vehicle (it is to be hoped that this was with a quick-release knot, and it wouldn’t be a method recommended today), or simply encouraging the dog by voice when it took the desired position. It has been said that Dalmatians of some lines preferred a particular position and tended to go to it naturally. Information about carriage work can be seen at the websites of the Dalmatian Club of America and the British Carriage Dog Society and on their Facebook pages. The Dalmatian Club of America holds road trials in the US, and the British Carriage Dog Society organizes carriage dog trials in the UK. A 1914 article in the magazine Country Life in America on training farm dogs suggests that the dog be trained to travel under the wagon when going to town, so that trouble with other dogs along the way might be avoided; in town, the dog would provide protection for the wagon. A book on the Catahoula (a smooth-haired stockdog breed from Louisiana) mentions a dog of this breed naturally keeping a precise position under the wagon. My German Shepherd, Wolf, predecessor of Pascha and Shasta, had a tendency to naturally keep a position in front of my pony when I went for a drive, and I'm sure he could have been easily trained to be fairly reliable at it (the position in front can be a little tricky for the dog on turns). Pascha and Shasta already had formal obedience training, which was very useful in their carriage dog training. They both quickly picked up what I wanted. Because of their heeling work, they already understood the concepts of keeping position and sitting automatically at a halt, and they would stay in place on command. I also taught them to ride quietly in the vehicle. Their first coaching lessons were on a quiet street and in a ring. I was helped by a friend and we used her road cart and Pony of the America, Pepper. The low-set road cart was ideal for training because I could be fairly close to Pascha and he could get well up under the seat, between the wheels with nose near the axle. Working with each dog individually, I first introduced the dog to the horse and vehicle, the dog on lead, allowing the dog and the horse to become acquainted with one another. Then my friend drove the road cart with the pony at a walk while I led the dog behind, guiding him or her in the proper position. After a little of this, I put the dog into a sit-stay behind the cart, ran the lead over the back of the seat, and climbed in. Holding the lead and concentrating on the dog while my friend dove the pony, we started off at a slow walk. At first the dog would zig-zag and try go around the wheel to the side of the vehicle, not understanding what was wanted, but I would guide the dog back into position with the lead until the dog began to understand what I wanted. Then we worked on a loose lead, and when the dog was doing well, we worked off-lead. Soon both dogs were maintaining position at various gaits end doing automatic sits at the stop. Gradually, faster speeds, more frequent changes of gait, and sharper turns were introduced. It worked out very well—while I was giving the dog coaching practice, my friend could give her pony driving practice.

The usual road gait is a trot of varying speeds for both pony and dog. When the pony really trots out, the dog goes into a gallop. Coaching would be a great way to condition dogs. When the dog has worked enough, it can then come aboard for a ride. In actual road-work, the dog is working quite a lot on its own and has to do automatic starts as well as automatic halts. Reliability is important because the driver's attention has to be on the horse. As is the case when driving with no dogs involved, taking a passenger along to help out in an emergency is practically a necessity. There are few areas available for horse-drawn vehicles that are free of such hazards as traffic, resident dogs on the loose, or anything unexpected to which an equine might object. When doing their carriage work, Shasta or Pascha were to remain in place while we entered and exited the cart. For long stops, they were to stay in position as in the long sits and downs of obedience competition. They entered and exited the vehicle when directed. I used "load" for enter and "out" for exit. "Coach" was the equivalent of "heel," and other commands were the same as in obedience. The commands need to be different from the commands given to the horse so there aren't any conflicts. "Get in" said to the dog might sound too much like "Get up" to the horse, leading to an awkward situation. But it is no problem for each animal to think that the praise is for him or her. To teach the dogs to "load," we first showed them the way with the cart unhitched. They needed to learn to get in and out of the cart quickly and smoothly, and only with permission. Inside the cart the dog sits quietly on the floorboard, alertly watching the passing scene. Whether riding in the cart of following along, some dogs will want to "tell off" other dogs when they see them, but this shouldn’t be allowed. The problems in trying to sort out a bunch of dogs while driving a pony cart can be imagined. Both Shasta and Pascha especially loved riding in the cart. This wasn’t Pascha’s first experience as a carriage passenger, actually – he had accompanied us on a carriage tour of Seville a few years earlier when we had taken him with us when visiting Spain. A subsequent move of my own pony to a location with fewer places for driving led to a curtailment of our carriage dog activities, but I hope to be able to train a new carriage-dog student some day.

Pascha in the cart, sitting on the floor, his head just visible, going on a ride provided by Meadowlawn Penny, my Section B Welsh Pony. At right: Pascha -- Glengyle Frost Bi Moonlight, UD, OTD-s, HT. |