Sheepdog Training in 18th Century France

Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton (1716 –1799) was a French naturalist who assisted George-Louis Leclerc de Buffon with Buffon’s famous natural history work, the Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière. He also was instrumental in the importation of Merino sheep into France, where they became the basis for the Rambouillet breed. Daubenton lectured on natural history in the College of Medicine and on rural economy at the Alfort school. In 1782 he published Instruction pour les Bergers et les Propriétaires de Troupeaux, which appeared in an English translation in 1811 as Advice to Shepherds and Owners of Flocks on the Care and Management of Sheep. The book is in the form of a series of questions and answers. Among the topics he covered were the qualifications needed by a good shepherd and the handling and training of shepherds’ dogs.

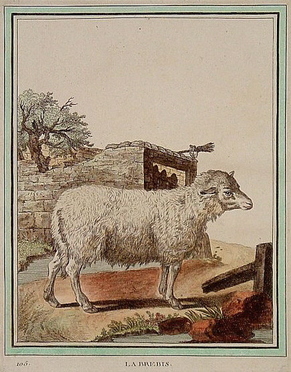

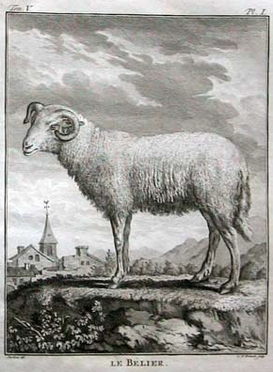

From Buffon’s Natural History, 18th century:

The shepherd's dog

The shepherd's dog

from INSTRUCTION POUR LES BERGERS (Advice for Shepherds)

by Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton

CHAPTER I.

ON THE QUALIFICATIONS OF A SHEPHERD.

by Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton

CHAPTER I.

ON THE QUALIFICATIONS OF A SHEPHERD.

Question. What should be the age of a shepherd to take charge of a flock of sheep?

Answer. His age is of no importance, if he is strong enough to carry the hurdles for the pen, and considerate enough to mind his business, instead of playing with his comrades.

Q. Will the business of a shepherd employ a man his whole time, and enable him to obtain an honest livelihood?

A. A careful and well informed shepherd, who has the care of a large flock, is almost continually employed in conducting it properly during the day, in folding it for the night, in feeding it in bad weather, in keeping it clean, in treating its diseases, &c. Shepherds receive good wages and are well paid in countries, where sheep are maintained, that is, when they know their business, and will carefully perform it.

Q. Are many qualifications necessary to become a good shepherd?

A. More things are necessary to be known in the business of a shepherd than in most other agricultural employments. A good shepherd should understand the best method of folding, feeding, watering, and pasturing his flock, of treating its diseases, and improving it, as well in the breed, as in the quality and fineness of the wool; to drive, wash, and shear his flock in the best manner; to rear and train dogs, and keep them in subjection, and to protect the flock against wolves, and other noxious animals.

Q. How can it be known that a young man will make a good shepherd?

A. A good shepherd may be expected from one who understands and retains what is told him as well as other young men in the country; if he is careful and patient, and has no infirmity, which will hinder him from walking or standing for a length of time together.

Q. Is it necessary that a shepherd should know how to read?

A. One, who understands reading, more readily acquires information, but it is not absolutely necessary; he however, would be the more valuable for knowing how to read, write, and cypher.

Q. With what necessaries should a shepherd be provided to manage his flock in the fields?

A. He should be well clothed, so as to continue the whole day in the field, without suffering much from cold, or from being exposed for a long time in the rain, without being wet to the skin. He should have a crook, a whip, a scratcher, a knife, a lancet, a tin box prepared with a suitable ointment, and a scrip.

. . .

Q. What is a crook, and for what purpose is it used?

A. The crook is a staff about six feet long, terminated on the upper end by an iron, which is in the form of a small spade, and on the other end by a hook bent back on the top; the hook may be put on the side of the flat iron, and then it should be bent inward. The flat iron of the crook is intended to throw earth near the sheep, which stray from the flock, so as to make them return. The hook is made for seizing and catching them by one of the hind legs.

Q. What is a shepherd's scrip, and for what purpose is it used?

A. A scrip is a pocket or knapsack, attached to a leather string, which the shepherd carries like a shoulder belt. He puts, in his scrip, his provisions for the day, a box of ointment to rub such sheep as he sees scratching themselves in the field; a scratcher to remove the scabs of the itch before applying the ointment; a lancet to bleed such sheep as may require it; a small knife to skin, and to open such as may die in the field, &c.

Q. Is it necessary to have a scratcher, knife, and lancet in separate instruments?

A. A single instrument is sufficient, that is, a small knife, which shuts on its handle, the end of the handle being flattened and brought to an edge, makes a scratcher; the blade, being pointed, and sharp on both sides, near the point, serves as a lancet.

Answer. His age is of no importance, if he is strong enough to carry the hurdles for the pen, and considerate enough to mind his business, instead of playing with his comrades.

Q. Will the business of a shepherd employ a man his whole time, and enable him to obtain an honest livelihood?

A. A careful and well informed shepherd, who has the care of a large flock, is almost continually employed in conducting it properly during the day, in folding it for the night, in feeding it in bad weather, in keeping it clean, in treating its diseases, &c. Shepherds receive good wages and are well paid in countries, where sheep are maintained, that is, when they know their business, and will carefully perform it.

Q. Are many qualifications necessary to become a good shepherd?

A. More things are necessary to be known in the business of a shepherd than in most other agricultural employments. A good shepherd should understand the best method of folding, feeding, watering, and pasturing his flock, of treating its diseases, and improving it, as well in the breed, as in the quality and fineness of the wool; to drive, wash, and shear his flock in the best manner; to rear and train dogs, and keep them in subjection, and to protect the flock against wolves, and other noxious animals.

Q. How can it be known that a young man will make a good shepherd?

A. A good shepherd may be expected from one who understands and retains what is told him as well as other young men in the country; if he is careful and patient, and has no infirmity, which will hinder him from walking or standing for a length of time together.

Q. Is it necessary that a shepherd should know how to read?

A. One, who understands reading, more readily acquires information, but it is not absolutely necessary; he however, would be the more valuable for knowing how to read, write, and cypher.

Q. With what necessaries should a shepherd be provided to manage his flock in the fields?

A. He should be well clothed, so as to continue the whole day in the field, without suffering much from cold, or from being exposed for a long time in the rain, without being wet to the skin. He should have a crook, a whip, a scratcher, a knife, a lancet, a tin box prepared with a suitable ointment, and a scrip.

. . .

Q. What is a crook, and for what purpose is it used?

A. The crook is a staff about six feet long, terminated on the upper end by an iron, which is in the form of a small spade, and on the other end by a hook bent back on the top; the hook may be put on the side of the flat iron, and then it should be bent inward. The flat iron of the crook is intended to throw earth near the sheep, which stray from the flock, so as to make them return. The hook is made for seizing and catching them by one of the hind legs.

Q. What is a shepherd's scrip, and for what purpose is it used?

A. A scrip is a pocket or knapsack, attached to a leather string, which the shepherd carries like a shoulder belt. He puts, in his scrip, his provisions for the day, a box of ointment to rub such sheep as he sees scratching themselves in the field; a scratcher to remove the scabs of the itch before applying the ointment; a lancet to bleed such sheep as may require it; a small knife to skin, and to open such as may die in the field, &c.

Q. Is it necessary to have a scratcher, knife, and lancet in separate instruments?

A. A single instrument is sufficient, that is, a small knife, which shuts on its handle, the end of the handle being flattened and brought to an edge, makes a scratcher; the blade, being pointed, and sharp on both sides, near the point, serves as a lancet.

CHAPTER II.

OF DOGS AND WOLVES.

OF DOGS AND WOLVES.

Q. Is it necessary, that shepherds should have dogs for driving their flocks?

A. It is to be wished, that shepherds could dispense with them, because they often do much mischief; but they are necessary in countries, where the lands are often sown with corn, and exposed to injury: when sheep stray from the flock, the shepherd can restrain those only, which are near him, and at the distance, at which, he can throw lumps of earth before them with his crook : dogs, therefore, assist the shepherd in driving his flock, and defend it against wolves, when strong enough.

Q. In what countries can a shepherd manage his flock without the aid of dogs?

A. In places, where the land is divided into large enclosures, there is always a great deal of ground in fallow, that is, not sown; a numerous flock can be there conducted without the aid of dogs. Sheep naturally go together; they do not stray from the flock, except they observe a better pasture, than where they are; this allurement is commonly too far from great fallows, to attract them; but if the flock should be on one end of a fallow, near land liable to injury, the shepherd places himself on the side of such lands, to protect them.

Q. What injury can dogs do sheep, and how can they be restrained?

A. Dogs badly disciplined, and too ardent, fly upon the sheep, bite and wound them, and cause abscesses. They frighten the ewes with young, by hurting them, and making them miscarry. They throw down the weak, and such as can hardly follow the flock, or fatigue and fret them, by driving them too fast. To prevent these inconveniences, it is proper to make use of such dogs only in driving as are mild and good natured, and well trained to shew their teeth to wolves, but not to sheep. A good well-bred dog makes them obey without hurting them. Sheep are accustomed to do of themselves, what the dog would compel them to, by force. They withdraw when he approaches, and do not advance on the side, where they see him a sentinel, on the borders of a prohibited ground.

Q. How do dogs serve to direct the course of a flock?

A. When a shepherd drives his flock before him, he can greatly hasten its speed, and that of the sheep, which remain behind ; but he cannot prevent it from going too quick, nor the sheep from running forward too fast, or straying to the right or left; it is necessary, he should have the aid of dogs, to place round the flock, to send forward, or to restrain such as go too fast, to bring up those which remain behind, or stray to the right or left.

Q. How can a shepherd make his dog perform these different manoeuvres?

A. He must train them from their youth, and accustom them to obey his voice. The dog goes on all sides; before the flock to stop it; behind it, to make it go forward; on the sides, to prevent it from straying: he remains at his post, or returns to the shepherd, according to signs given him, which he understands.

Q. What is necessary to be done to train a shepherd's dog?

A. He must be learnt to stop, to lie down, to bark, to stop barking, to place himself on the side of the flock, to walk round it, and to seize a sheep by the ear, at the command of the shepherd, when given him by the sound of his voice, or by the motion of his hand.

Q. How is a dog taught to stop, or lie down, at command?

A. By pronouncing the word stop, a piece of bread or other food should be given him, which makes him stop, or he is stopped by force ; by repeating this manoeuvre, he is accustomed to stop, at the sound of the voice. To teach him to lie down, when required, it is necessary to caress him, when he does it of himself ; or after having obliged him to it, by taking him by the legs and pronouncing the words lie down ; if he would rise too soon, he is chastised, to make him remain. When he is quiet, they give him something to eat, and by these means he is made to obey.

Q. How do they make a dog bark, or stop barking, at command?

A. The barking of the dog is to be imitated, while he is shown a piece of bread, which is given him, as soon as he has barked, when the word bark is repeated: he is accustomed also to stop barking, when the world silence is pronounced: he is threatened or chastised, when he does not obey, and rewarded and caressed, when he does.

A. It is to be wished, that shepherds could dispense with them, because they often do much mischief; but they are necessary in countries, where the lands are often sown with corn, and exposed to injury: when sheep stray from the flock, the shepherd can restrain those only, which are near him, and at the distance, at which, he can throw lumps of earth before them with his crook : dogs, therefore, assist the shepherd in driving his flock, and defend it against wolves, when strong enough.

Q. In what countries can a shepherd manage his flock without the aid of dogs?

A. In places, where the land is divided into large enclosures, there is always a great deal of ground in fallow, that is, not sown; a numerous flock can be there conducted without the aid of dogs. Sheep naturally go together; they do not stray from the flock, except they observe a better pasture, than where they are; this allurement is commonly too far from great fallows, to attract them; but if the flock should be on one end of a fallow, near land liable to injury, the shepherd places himself on the side of such lands, to protect them.

Q. What injury can dogs do sheep, and how can they be restrained?

A. Dogs badly disciplined, and too ardent, fly upon the sheep, bite and wound them, and cause abscesses. They frighten the ewes with young, by hurting them, and making them miscarry. They throw down the weak, and such as can hardly follow the flock, or fatigue and fret them, by driving them too fast. To prevent these inconveniences, it is proper to make use of such dogs only in driving as are mild and good natured, and well trained to shew their teeth to wolves, but not to sheep. A good well-bred dog makes them obey without hurting them. Sheep are accustomed to do of themselves, what the dog would compel them to, by force. They withdraw when he approaches, and do not advance on the side, where they see him a sentinel, on the borders of a prohibited ground.

Q. How do dogs serve to direct the course of a flock?

A. When a shepherd drives his flock before him, he can greatly hasten its speed, and that of the sheep, which remain behind ; but he cannot prevent it from going too quick, nor the sheep from running forward too fast, or straying to the right or left; it is necessary, he should have the aid of dogs, to place round the flock, to send forward, or to restrain such as go too fast, to bring up those which remain behind, or stray to the right or left.

Q. How can a shepherd make his dog perform these different manoeuvres?

A. He must train them from their youth, and accustom them to obey his voice. The dog goes on all sides; before the flock to stop it; behind it, to make it go forward; on the sides, to prevent it from straying: he remains at his post, or returns to the shepherd, according to signs given him, which he understands.

Q. What is necessary to be done to train a shepherd's dog?

A. He must be learnt to stop, to lie down, to bark, to stop barking, to place himself on the side of the flock, to walk round it, and to seize a sheep by the ear, at the command of the shepherd, when given him by the sound of his voice, or by the motion of his hand.

Q. How is a dog taught to stop, or lie down, at command?

A. By pronouncing the word stop, a piece of bread or other food should be given him, which makes him stop, or he is stopped by force ; by repeating this manoeuvre, he is accustomed to stop, at the sound of the voice. To teach him to lie down, when required, it is necessary to caress him, when he does it of himself ; or after having obliged him to it, by taking him by the legs and pronouncing the words lie down ; if he would rise too soon, he is chastised, to make him remain. When he is quiet, they give him something to eat, and by these means he is made to obey.

Q. How do they make a dog bark, or stop barking, at command?

A. The barking of the dog is to be imitated, while he is shown a piece of bread, which is given him, as soon as he has barked, when the word bark is repeated: he is accustomed also to stop barking, when the world silence is pronounced: he is threatened or chastised, when he does not obey, and rewarded and caressed, when he does.

Ewe and ram from Buffon’s Natural History, 18th Century

Q. At what age is it proper to train dogs for the use of a shepherd?

A. They begin training them when six months old, if they have been well fed, and are strong; but if they are weak, it is necessary to wait, until they are nine months old.

Q. How is a dog made to go round a flock, to pass on its side, to run before, to come back, or to remain in his place?

A. To learn a dog to go round, a stone must be thrown before him, and then successively from place to place, until he shall have gone round the flock, always repeating the word turn, by throwing a stone before, and then behind him; he is trained to run on the side of a flock, by pronouncing the words, on the sides; they say, go, to make him go before; return, to make him return; stop, to continue in place; other words may be substituted, in places here shepherds have another language.

Q. How is a dog learnt to seize a sheep by the ear to bring him back when he wanders, or to stop him in the middle of the flock, to wait for the shepherd?

A. A dog is made to go round a single sheep in an enclosure: the ear of the sheep is put to the dog's mouth, to accustom him to seize the sheep thereby: or a piece of bread is tied to the ear of a sheep in the middle of a flock, when the dog is excited to aim thereat, and is thus habituated to seize the ear. In this manner a dog is taught to stop such sheep as the shepherd may shew him in the flock. Dogs may also be taught to stop sheep, by seizing them by the leg, before or behind, or above the fetlock: but this practice has its inconveniencies; the fetlock is often swelled by it, and the sheep made lame for some time.

Q. How does a dog make a flock obey him?

A. He makes the first sheep fly before him, by running at him, and then one after the other, the whole flock takes the same course, if the dog continues to press forward: when a sheep is not ready enough to obey him, he approaches and threatens him by barking.

Q. When a dog is well trained, can he instruct another?

A. It requires less time and trouble to teach a young dog, when he has the example of one, which knows how to drive the flock: the young dog will take the same gait, but he is often deceived; he would, perhaps, be never well taught, if the shepherd did not learn him such things, as the example of the other dog could not make him understand.

Q. What kind of dogs, and how many, are proper for the service of flocks?

A. All active docile dogs are good for training to the service; those are called dogs of the true breed, whose fathers and mothers are well practised in conducting flocks; it is thought, that dogs, thus bred, are more easily trained, than others. In parts of the country, where the lands are rarely exposed to be injured by sheep, a single dog is sufficient for an hundred sheep; but when they are so exposed, and are near to sheep walks, which the flock often approaches, two, and even three and four dogs are necessary; because two could not stand for the whole day, or for many successive days, the almost continual running, which they are obliged to make, to keep the sheep from the prohibited lands; it would therefore be necessary to have other dogs to relieve, and to give them rest, when much fatigued. In countries where wolves are to be apprehended, it is necessary, that the dogs should be strong enough to resist, and bold enough to hunt them. Dogs well covered with hair, support cold and rain better than others.

Q. What breed of dogs is preferred, in countries where wolves are little to be dreaded.

A. A breed of dogs called shepherds’ dogs, from being commonly used in the service of flocks; they are naturally active, and easily made docile: dogs of every other breed may be trained for the same purpose.

Q. What is the best breed of dogs for guarding sheep, where wolves are to be apprehended?

A. The mastiff breed is best: these dogs are strong and courageous; but it is necessary to give them collars armed with long iron points; and to incite them against the wolf, the first time they have to fight him, or to put them in company with other dogs trained to the business.

Q. What precautions are necessary, when you have a badly disciplined dog, that wounds the sheep?

A. The long canine teeth, which enter deep into the flesh, should be broken off, in case he bites.

Q. How ought shepherds’ dogs to be fed?

A. It costs but little to feed them, in the neighbourhood of large cities, where horse-meat, the scraps of tallow, &c. can be easily procured; for the want thereof, coarse bread must be made for them: it is improper to give them mutton; because, if they are accustomed to this feed, they will acquire the habit of biting the sheep, for the sake of the blood. Mastiffs are trained, like other dogs to driving sheep.

Q. Have not shepherds some means of driving their flocks when they have no dogs?

A. Shepherds teach some sheep of the flock, to which they give particular names, to come to them, at their call; and in order that they may take this habit, they are enticed to follow them by giving them pieces of bread. When the shepherd would make the flock pass a narrow path, or passage-way, on its route, or would collect his flock, he makes the tame sheep come to him; such as are near accompany them, others take the same course, and immediately the whole flock becomes disposed to follow the shepherd.

Q. What precautions should a shepherd take against wolves?

A. 1st. He should tie small bells to the necks of a certain number of sheep, which have strayed into the woods, and other places out of his sight. When a wolf approaches, the sheep are commonly the first to discover him; they are frightened an agitated in a manner, to make their bells heard, which disclose their danger, both to the dogs an shepherd. The little bells also call the shepherd, when something extraordinary happens in the flock, whether by night or by day, which puts the sheep in motion.—2nd. The shepherd takes care that his flock be accompanied by dogs strong and courageous enough to face a wolf, to put him to flight, to pursue, and even to kill him.—3rd. The shepherd carefully observes his flock, when it drives it near woods, or places frequented by wolves. The same attention should be paid when he is near fields, where the grass or growth is high enough to conceal them; they are always to be feared in foggy weather, and in the dusk of the evening, and above all, near hedges and bushes, where they keep themselves in ambush.—4th. Shepherds also make fires, or at least smoke, near their flocks.

Q. What ought the shepherd to do, when wolves approach the flock, or have seized upon some of the sheep?

A. When the wolf appears, the shepherd collects his flock, and sends his dogs in pursuit of him; he remains near the flock, to observe if he can see other wolves; halloos to the wolf, and encourages his dogs. But if the wolf has already seized his prey, the shepherd runs after him, without, however, losing sight of the flock, urges the dogs to the battle, and forces him to abandon his prey, which often happens.

. . .

A. They begin training them when six months old, if they have been well fed, and are strong; but if they are weak, it is necessary to wait, until they are nine months old.

Q. How is a dog made to go round a flock, to pass on its side, to run before, to come back, or to remain in his place?

A. To learn a dog to go round, a stone must be thrown before him, and then successively from place to place, until he shall have gone round the flock, always repeating the word turn, by throwing a stone before, and then behind him; he is trained to run on the side of a flock, by pronouncing the words, on the sides; they say, go, to make him go before; return, to make him return; stop, to continue in place; other words may be substituted, in places here shepherds have another language.

Q. How is a dog learnt to seize a sheep by the ear to bring him back when he wanders, or to stop him in the middle of the flock, to wait for the shepherd?

A. A dog is made to go round a single sheep in an enclosure: the ear of the sheep is put to the dog's mouth, to accustom him to seize the sheep thereby: or a piece of bread is tied to the ear of a sheep in the middle of a flock, when the dog is excited to aim thereat, and is thus habituated to seize the ear. In this manner a dog is taught to stop such sheep as the shepherd may shew him in the flock. Dogs may also be taught to stop sheep, by seizing them by the leg, before or behind, or above the fetlock: but this practice has its inconveniencies; the fetlock is often swelled by it, and the sheep made lame for some time.

Q. How does a dog make a flock obey him?

A. He makes the first sheep fly before him, by running at him, and then one after the other, the whole flock takes the same course, if the dog continues to press forward: when a sheep is not ready enough to obey him, he approaches and threatens him by barking.

Q. When a dog is well trained, can he instruct another?

A. It requires less time and trouble to teach a young dog, when he has the example of one, which knows how to drive the flock: the young dog will take the same gait, but he is often deceived; he would, perhaps, be never well taught, if the shepherd did not learn him such things, as the example of the other dog could not make him understand.

Q. What kind of dogs, and how many, are proper for the service of flocks?

A. All active docile dogs are good for training to the service; those are called dogs of the true breed, whose fathers and mothers are well practised in conducting flocks; it is thought, that dogs, thus bred, are more easily trained, than others. In parts of the country, where the lands are rarely exposed to be injured by sheep, a single dog is sufficient for an hundred sheep; but when they are so exposed, and are near to sheep walks, which the flock often approaches, two, and even three and four dogs are necessary; because two could not stand for the whole day, or for many successive days, the almost continual running, which they are obliged to make, to keep the sheep from the prohibited lands; it would therefore be necessary to have other dogs to relieve, and to give them rest, when much fatigued. In countries where wolves are to be apprehended, it is necessary, that the dogs should be strong enough to resist, and bold enough to hunt them. Dogs well covered with hair, support cold and rain better than others.

Q. What breed of dogs is preferred, in countries where wolves are little to be dreaded.

A. A breed of dogs called shepherds’ dogs, from being commonly used in the service of flocks; they are naturally active, and easily made docile: dogs of every other breed may be trained for the same purpose.

Q. What is the best breed of dogs for guarding sheep, where wolves are to be apprehended?

A. The mastiff breed is best: these dogs are strong and courageous; but it is necessary to give them collars armed with long iron points; and to incite them against the wolf, the first time they have to fight him, or to put them in company with other dogs trained to the business.

Q. What precautions are necessary, when you have a badly disciplined dog, that wounds the sheep?

A. The long canine teeth, which enter deep into the flesh, should be broken off, in case he bites.

Q. How ought shepherds’ dogs to be fed?

A. It costs but little to feed them, in the neighbourhood of large cities, where horse-meat, the scraps of tallow, &c. can be easily procured; for the want thereof, coarse bread must be made for them: it is improper to give them mutton; because, if they are accustomed to this feed, they will acquire the habit of biting the sheep, for the sake of the blood. Mastiffs are trained, like other dogs to driving sheep.

Q. Have not shepherds some means of driving their flocks when they have no dogs?

A. Shepherds teach some sheep of the flock, to which they give particular names, to come to them, at their call; and in order that they may take this habit, they are enticed to follow them by giving them pieces of bread. When the shepherd would make the flock pass a narrow path, or passage-way, on its route, or would collect his flock, he makes the tame sheep come to him; such as are near accompany them, others take the same course, and immediately the whole flock becomes disposed to follow the shepherd.

Q. What precautions should a shepherd take against wolves?

A. 1st. He should tie small bells to the necks of a certain number of sheep, which have strayed into the woods, and other places out of his sight. When a wolf approaches, the sheep are commonly the first to discover him; they are frightened an agitated in a manner, to make their bells heard, which disclose their danger, both to the dogs an shepherd. The little bells also call the shepherd, when something extraordinary happens in the flock, whether by night or by day, which puts the sheep in motion.—2nd. The shepherd takes care that his flock be accompanied by dogs strong and courageous enough to face a wolf, to put him to flight, to pursue, and even to kill him.—3rd. The shepherd carefully observes his flock, when it drives it near woods, or places frequented by wolves. The same attention should be paid when he is near fields, where the grass or growth is high enough to conceal them; they are always to be feared in foggy weather, and in the dusk of the evening, and above all, near hedges and bushes, where they keep themselves in ambush.—4th. Shepherds also make fires, or at least smoke, near their flocks.

Q. What ought the shepherd to do, when wolves approach the flock, or have seized upon some of the sheep?

A. When the wolf appears, the shepherd collects his flock, and sends his dogs in pursuit of him; he remains near the flock, to observe if he can see other wolves; halloos to the wolf, and encourages his dogs. But if the wolf has already seized his prey, the shepherd runs after him, without, however, losing sight of the flock, urges the dogs to the battle, and forces him to abandon his prey, which often happens.

. . .

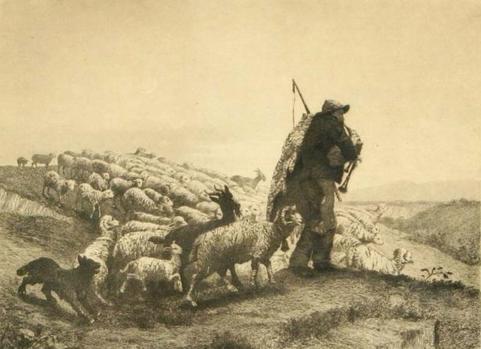

Merino sheep with a goat;

from a 19th century edition of Buffon’s Natural History

from a 19th century edition of Buffon’s Natural History

CHAPTER V.

CONCERNING THE MANAGEMENT OF SHEEP IN PASTURES.

CONCERNING THE MANAGEMENT OF SHEEP IN PASTURES.

Q. What are the principal rules which shepherds should observe, in grazing their flocks?

A. They may be reduced to seven.

1st. To graze them every day, if possible.

2d. Not to stop them too often while grazing, except in closed pastures.

3d. To prevent them from doing damage, when grazing on lands liable to injury.

4th. To avoid moist soils, and grass covered with dew or white frost.

5th. To put the flock in the shade, during the sun's greatest heat; and to drive it in the morning as much as possible, on the side lands, exposed to the west, and in the evening, to such as present to the east.

6th. To remove the flock from grasses, which may prove hurtful to them.

7th. And to drive it slowly, particularly when ascending hills.

Q. Why should sheep be made to graze every day?

A. Because it is the most natural, and least costly manner of feeding them; and which can be but imperfectly done, by giving them fodder at the rack. In grazing, they have a choice of food, and take it in the best state; grass is always much better for them, than hay or straw. Even if food could not be found in the field, the exercise they would receive in walking, would give them an appetite for their fodder.

Q. Why are sheep allowed to wander, while pasturing?

A. Because it would disturb, to stop them when grazing: it is their natural disposition, in seeking their food to wander from place to place; this exercise preserves their vigour.

Q. Why are not sheep allowed to graze in enclosed pastures, as in open fields ?

A. Because sheep, when allowed to run over a rich pasture, spoil more grass with their feet than they eat. To preserve the feed, the flock should be allowed every day, only such part of it, as it may consume. The flock should be fenced in, by a pen, or fold, within which, there should be grass enough for the number of sheep; the next day the pen should be shifted, and so successively, until the flock shall have eaten the whole pasture.

. . .

Q. Why should a shepherd always drive his flock moderately, especially when ascending hills?

A. Because, in driving his flock too quick, especially on ascending ground, he would run the risk of heating many of the sheep, to the degree of making them sick, and even destroying them.

Q. How ought the shepherd to manage his flock, when driving it?

A. He ought to prevent any animal from separating from the flock, by running before, remaining behind, or straying to the right or left.

Q. How can a shepherd do all that?

A. By the aid of his whip, his crook, and his dogs; when he makes his flock go before him, he drives the sheep behind, with his whip: the dog is before, and restrains the sheep from going forward too fast: the shepherd menaces those that stray to the right or left, to make them return to the flock, or if he has a dog behind him, he sends him after the sheep, which stray, to bring them back, or makes them return, by throwing a little dirt at them, so as never to touch their bodies, which is improper.

Q. How does he set the flock forward again?

A. He speaks to the dog, which is before, to let them advance, and then drives forward the hinder sheep; he can make them go forward, or return by speaking to them in different tones, to which he accustoms them.

Q. Can a shepherd conduct his flock by going before?

A. Yes, if he has at least one dog, on which he can depend, to prevent any part of the flock straying behind, or on the sides. The flock follows the shepherd even better than the dog, but it is necessary he should have regard to the sheep, behind.

Q. How does the shepherd make the flock pass a narrow passage, or a bad track?

A. The shepherd causes some animals to follow him, which he has accustomed to come to him at his call: he goes first, and calls them, in order to induce them to follow him; the first, which pass, are followed by the rest. If there should be no sheep in the flock, acquainted with his call, he should present a piece of bread to such, as are most ready to take it, and in this way, he can make the whole flock to follow him.

Q. How does a shepherd prevent his flock from doing damage to grounds sown to grain?

A. When the flock is near such grounds, he sends a dog upon the edge of the field sown, to prevent any of the sheep from approaching it: if there is a like field on the other side, he sends another dog, if he has another; or goes thither himself.

Q. How does the shepherd manage when he has no dog, and has two fields to guard?

A. Whilst he guards one of the fields, he speaks to the animals, which go upon the other, to make them quit it; if they do not obey, he should run after them, and drive them out. But it is necessary that a shepherd should have, at least, one dog, when he conducts a flock near grounds sown to grain; but a dog is not so necessary, where there are great fallows.

Q. What can the shepherd do, to retain his flock in a place, where the feed is good?

A. He induces his flock to continue, if he stays there himself with his dogs, and plays upon some instrument, such as the flageolet, the flute, the hautbois [oboe], or the bag-pipe, &c. Sheep are pleased with the sound of instruments, and feed quietly, while the shepherd is playing thereon.

A. They may be reduced to seven.

1st. To graze them every day, if possible.

2d. Not to stop them too often while grazing, except in closed pastures.

3d. To prevent them from doing damage, when grazing on lands liable to injury.

4th. To avoid moist soils, and grass covered with dew or white frost.

5th. To put the flock in the shade, during the sun's greatest heat; and to drive it in the morning as much as possible, on the side lands, exposed to the west, and in the evening, to such as present to the east.

6th. To remove the flock from grasses, which may prove hurtful to them.

7th. And to drive it slowly, particularly when ascending hills.

Q. Why should sheep be made to graze every day?

A. Because it is the most natural, and least costly manner of feeding them; and which can be but imperfectly done, by giving them fodder at the rack. In grazing, they have a choice of food, and take it in the best state; grass is always much better for them, than hay or straw. Even if food could not be found in the field, the exercise they would receive in walking, would give them an appetite for their fodder.

Q. Why are sheep allowed to wander, while pasturing?

A. Because it would disturb, to stop them when grazing: it is their natural disposition, in seeking their food to wander from place to place; this exercise preserves their vigour.

Q. Why are not sheep allowed to graze in enclosed pastures, as in open fields ?

A. Because sheep, when allowed to run over a rich pasture, spoil more grass with their feet than they eat. To preserve the feed, the flock should be allowed every day, only such part of it, as it may consume. The flock should be fenced in, by a pen, or fold, within which, there should be grass enough for the number of sheep; the next day the pen should be shifted, and so successively, until the flock shall have eaten the whole pasture.

. . .

Q. Why should a shepherd always drive his flock moderately, especially when ascending hills?

A. Because, in driving his flock too quick, especially on ascending ground, he would run the risk of heating many of the sheep, to the degree of making them sick, and even destroying them.

Q. How ought the shepherd to manage his flock, when driving it?

A. He ought to prevent any animal from separating from the flock, by running before, remaining behind, or straying to the right or left.

Q. How can a shepherd do all that?

A. By the aid of his whip, his crook, and his dogs; when he makes his flock go before him, he drives the sheep behind, with his whip: the dog is before, and restrains the sheep from going forward too fast: the shepherd menaces those that stray to the right or left, to make them return to the flock, or if he has a dog behind him, he sends him after the sheep, which stray, to bring them back, or makes them return, by throwing a little dirt at them, so as never to touch their bodies, which is improper.

Q. How does he set the flock forward again?

A. He speaks to the dog, which is before, to let them advance, and then drives forward the hinder sheep; he can make them go forward, or return by speaking to them in different tones, to which he accustoms them.

Q. Can a shepherd conduct his flock by going before?

A. Yes, if he has at least one dog, on which he can depend, to prevent any part of the flock straying behind, or on the sides. The flock follows the shepherd even better than the dog, but it is necessary he should have regard to the sheep, behind.

Q. How does the shepherd make the flock pass a narrow passage, or a bad track?

A. The shepherd causes some animals to follow him, which he has accustomed to come to him at his call: he goes first, and calls them, in order to induce them to follow him; the first, which pass, are followed by the rest. If there should be no sheep in the flock, acquainted with his call, he should present a piece of bread to such, as are most ready to take it, and in this way, he can make the whole flock to follow him.

Q. How does a shepherd prevent his flock from doing damage to grounds sown to grain?

A. When the flock is near such grounds, he sends a dog upon the edge of the field sown, to prevent any of the sheep from approaching it: if there is a like field on the other side, he sends another dog, if he has another; or goes thither himself.

Q. How does the shepherd manage when he has no dog, and has two fields to guard?

A. Whilst he guards one of the fields, he speaks to the animals, which go upon the other, to make them quit it; if they do not obey, he should run after them, and drive them out. But it is necessary that a shepherd should have, at least, one dog, when he conducts a flock near grounds sown to grain; but a dog is not so necessary, where there are great fallows.

Q. What can the shepherd do, to retain his flock in a place, where the feed is good?

A. He induces his flock to continue, if he stays there himself with his dogs, and plays upon some instrument, such as the flageolet, the flute, the hautbois [oboe], or the bag-pipe, &c. Sheep are pleased with the sound of instruments, and feed quietly, while the shepherd is playing thereon.

The Contented Shepherd, c1660,

by David Teniers the Younger

by David Teniers the Younger

Return of the Flock in Provence, 1882,

by Paul Vayson

by Paul Vayson