WORKING WITH GEESE

Geese aren’t as common as some of the other types of livestock and many people may hesitate to work geese with their dog, associating them with the big bad-tempered goose they may have heard about in family stories or which even may have chased them during a long-ago visit to grandma's farm. But geese have much to recommend them.

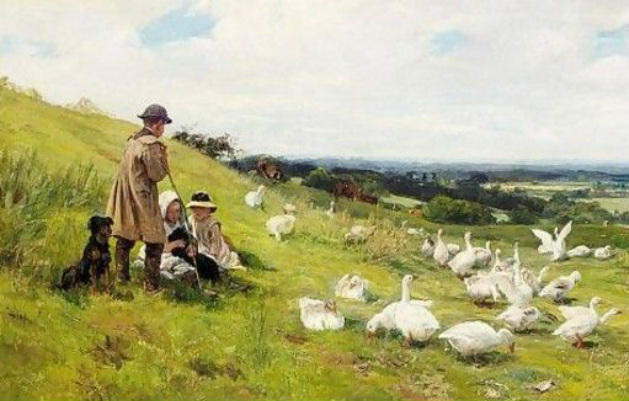

Geese have a long history of being herded. Watching over flocks of geese was a job frequently given to children. Dogs have been used in the handling of geese. Captain Max Von Stephanitz, in his book The German Shepherd Dog in Word and Picture, related:

|

“In the East they [the shepherd dogs] are also used for tending large flocks of geese. The dog for such work must be carefully selected, for a goose is very short-tempered and has a very good idea about how to use its beak, but it cannot stand any grip. In former times when the geese in large flocks waddled from Posen to the Berlin market, shepherd dogs generally trotted along with them to drive them.”

|

Arthur Allen, a noted American Border Collie trainer, told of the droving work his father did the late 1890s/early 1900s:

|

“The livestock dealer that my father was working for saw the possibility of extending his business and the opportunity of using my father and his dogs. In as much as, all farm families raised geese to supplement the family income and buy winter clothes, there were thousands of geese for sale each fall. He would scout the country and contract the geese, to be gathered at a later date, to be herded to Shawneetown [in southern Illinois] to be sold, a distance of about 65 miles. They used two wagons, one a campwagon and the other one loaded with corn to feed the geese and to help settle them for the night. Traveling this great distance many of the geese would get sore feet and for this they carried bucket or pine tar. The lame geese would be caught and their feet dipped in the pine tar. The tar was not only a healing agent but would pick up bits of dead grass and leaves, forming a protective coat on the goose's foot. In short the goose would have a new pair of shoes.”

From A Lifetime with the Working Collie, Their Training and History, 1979, by Arthur Allen |

Another method of preparing geese for a journey to market was to first walk them through a shallow pool of tar and then through some sand, which made a hard covering to protect their feet on the road.

Up until the 1970s when pesticides came into greater use, geese frequently were used for weeding crops, particularly in the cotton fields of the southern U.S., where a variety of “weeder goose” called the Cotton Patch Goose was developed. Weeding was done by geese in large crop fields in California as well. In most cases the geese were simply left in the field to do their work, with movement encouraged by placement of water containers, but in some cases geese were tended by children, sometimes with dogs. By encouraging the birds to move along, the whole field would be covered rather than the birds deciding to settle down in a more limited area. On some organic farms in recent years there has been a small revival in the use of geese as weeders. While large goose producers don’t generally use dogs to handle their geese, there are still some people who work their geese with dogs in practical situations, whether in larger flocks or just a few geese kept on a small mixed-use farm.

Up until the 1970s when pesticides came into greater use, geese frequently were used for weeding crops, particularly in the cotton fields of the southern U.S., where a variety of “weeder goose” called the Cotton Patch Goose was developed. Weeding was done by geese in large crop fields in California as well. In most cases the geese were simply left in the field to do their work, with movement encouraged by placement of water containers, but in some cases geese were tended by children, sometimes with dogs. By encouraging the birds to move along, the whole field would be covered rather than the birds deciding to settle down in a more limited area. On some organic farms in recent years there has been a small revival in the use of geese as weeders. While large goose producers don’t generally use dogs to handle their geese, there are still some people who work their geese with dogs in practical situations, whether in larger flocks or just a few geese kept on a small mixed-use farm.

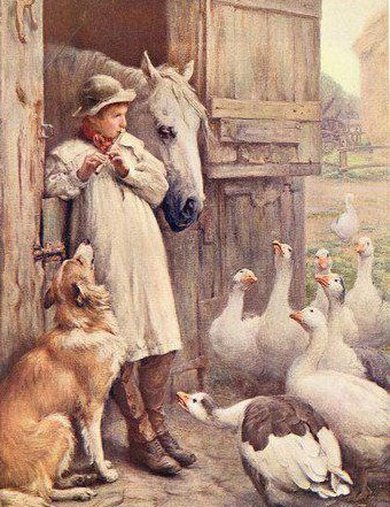

Otto Weber, "The Goose Girls," 19th century

The breeds I am most familiar with are the Tufted Roman, Pilgrim, American Buff, the rare Shetland goose, and a new breed, the Oregon Mini Goose. The Shetland goose is a small breed that, like the Pilgrim, is color-differentiated by sex, with the males being white in both breeds while Shetland females are grey and white and Pilgrim females are mostly grey. The Oregon Minis are likewise small geese, but with a more variable appearance due to different breeds that figured in their background; they come in a number of colors and patterns, and some even have some curly feathers due to the Sebastopol goose being one of the breeds used in their development. These small and medium-sized breeds are generally good-tempered, sensible, and will move better and have more stamina than heavier breeds such as the large white Emden, which is known for its sharp temper, and the big grey Toulouse, although some geese of these larger breeds have been fine also. Chinese and African geese (despite its name, the African goose is actually a variety of the Chinese goose) have been described as being particularly noisy and high strung, with a notable tendency to dramatically flare out their wings and honk loudly, although there are people who have worked them with their dogs and like them. The Sebastopol goose, a breed with unique curly feathers, is a favorite of one trainer, who writes, “They move softly, flock loosely, are quiet and don't seem to pattern which makes them great for demonstrations. They are a midsized goose, cannot fly, very gentle, and seem to handle crowd and dog pressure very well. The only time they are aggressive is when the geese are setting, then the entire flock is on edge. They also community-raise any goslings that hatch which makes working them during that time very difficult. It is the only time I have ever seen one stand up to a dog.”

While there are general temperament characteristics associated with various breeds, there is much variation even within a breed. The hatchery from which the geese come can make a difference. The Buff geese I worked with have been medium-sized and mild-mannered. Another experienced goose-owner found her Buffs, from a different hatchery, to be very large and heavy, lacking in stamina due to their weight, inclined to fly when startled despite their size, and not as satisfactory as some of her other breeds. Breed standards describe the Roman as small, the Pilgrim as medium-sized, and the Buff as larger than the other two, but in the case of the hatchery from which our geese came – a production breeder rather than a show-oriented breeder -- there have been large Romans, small Buffs, and the temperaments have been pretty much the same, fairly even and rarely obstreperous.

The Shetland geese in our flock were similar to our other geese in behavior, although a little higher-strung and with a tendency to move more quickly. Nonetheless, they worked well for a quiet dog that kept a suitable distance, and when working as part of a larger flock would stay right with the others. The Oregon Minis have proven to be nice to work with, having a convenient smaller size and calm temperament.

All geese, with their sense of dignity and good sense of self, appreciate polite handling.

While there are general temperament characteristics associated with various breeds, there is much variation even within a breed. The hatchery from which the geese come can make a difference. The Buff geese I worked with have been medium-sized and mild-mannered. Another experienced goose-owner found her Buffs, from a different hatchery, to be very large and heavy, lacking in stamina due to their weight, inclined to fly when startled despite their size, and not as satisfactory as some of her other breeds. Breed standards describe the Roman as small, the Pilgrim as medium-sized, and the Buff as larger than the other two, but in the case of the hatchery from which our geese came – a production breeder rather than a show-oriented breeder -- there have been large Romans, small Buffs, and the temperaments have been pretty much the same, fairly even and rarely obstreperous.

The Shetland geese in our flock were similar to our other geese in behavior, although a little higher-strung and with a tendency to move more quickly. Nonetheless, they worked well for a quiet dog that kept a suitable distance, and when working as part of a larger flock would stay right with the others. The Oregon Minis have proven to be nice to work with, having a convenient smaller size and calm temperament.

All geese, with their sense of dignity and good sense of self, appreciate polite handling.

Geese group well, but flock more loosely than ducks, being more like goats or cattle in that respect. Compared to ducks, especially Runner ducks, geese do not easily panic, being generally more similar in that respect to Call ducks. They will readily split if feeling pressured, however. They react well to a dog that works smoothly and quietly, and don't like a lot of bouncing around, barking, erratic moving, and pushing. If worked too roughly, they will raise their wings, run, or may come to bay and attempt to defend themselves. They don't like to be crowded together in small spaces. To work geese well, the dog should have a good sense of distance and rate, be able to apply steady but easy pressure, and have a good stop. If the dog is inattentive or isn't covering well, geese will quickly take advantage, separating and moving off to regroup elsewhere.

In my experience, our geese have worked best in groups of around 6 to 10 or more. They can be worked in smaller groups, but they become uneasy in small groups and more finesse will be required if splitting is to be avoided. One trainer experienced with geese relates that in groups larger than 10 or so, her geese don't flow as well and become harder to move, but I didn't find that to be the case with our geese. We regularly worked them in groups of 20 or 30 with a single dog. Although the dog may need to move around a bit more to cover the whole group, and the group may spread out too much if the dog doesn't cover them well, overall they moved well even in the larger groups.

Our geese were not as inclined as ducks to cling to fences or show as much of an attraction to a draw point, although they would nonetheless show some tendency to move toward a strong draw. On occasion, sometimes due to being over-pressured, or wanting to return to their home area, and other times for reasons that aren’t readily apparent, a group will take off and run a short distance, stretching out their wings and even flying a little if they haven’t had their wings clipped. Even in that situation, however, they usually settle down again quickly and are easily regathered, after which they will move along as if nothing had happened. Geese turn well from a dog and unless stressed won’t usually try to run through a dog like Runner ducks often will. When approached correctly, with the dog sweeping quietly in from the side along the fence, they move well out of corners and off of fences, unless tired or stressed. Worked considerately, they do not become sour or course-trained. In warmer weather geese often don’t have a lot of stamina and will soon begin to pant, but are hardier overall and are better designed for long-distance walking than ducks. They should be given ample opportunity to drink when working, with a water bucket being provided for rest periods.

In accordance with their good sense of self-regard, geese may challenge a dog if they sense weakness on the first approach, but respond well to a confident dog and won't continually challenge. With their steady demeanor, they may not bring out a prey drive in a dog that flighty ducks might. Our geese have rarely threatened or pinched, unless near a nest during breeding season or cornered in a situation from which they don't think they can escape. We have had one or two males that became overprotective and would occasionally charge a dog, but even they could be worked by a strong but steady dog. When making a challenge, geese stretch out their necks and snake out their beaks, sometimes raising their wings. They will also raise their wings and sound off if they are feeling too much pressure. As well as nipping or biting, they can strike with their wings. Another consideration when working geese is to be aware that particular individuals will form strong attachments with others, so to the extent possible try to keep mates and friends together if a large group is being separated into smaller groups, otherwise they may become upset, call to one another and not settle well. It is best to avoid hand-raising geese because an individual may become too bonded to a human and become jealous and aggressive toward "outsiders" as it would be protective of its mate. Our male geese have quarreled with one another much less than ducks and we only had one incident of a particular goose being soundly rejected by the flock, but other flock owners have experienced more fighting, particularly in the spring, so removed the troublemakers and kept a higher ratio of females. For information on overall care and raising of geese, a good source is The Book of Geese by David Holderread.

Geese that are accustomed to being worked are not particularly afraid of people, but will avoid coming close rather than drawing to people like school sheep or some Call ducks will. Because of their reaction to erratic movements by a dog, they aren’t really suitable for starting beginner dogs, but for dogs coming along in their training, they are excellent for refining cover and for practicing driving and shedding. They will remain calm and give the handler time to set up properly for training different maneuvers. A willingness to stay where they are left is helpful when setting up to practice outruns.

Well-handled geese move with a calm, unhurried dignity. They will slow and even stop if the dog releases pressure, but don’t get as heavy as regularly-worked Call ducks. Geese usually will have a certain amount of flow, although they don’t tend to have an excessive amount of drift unless they are headed in a particular direction where they very much want to go. Even then, there usually is no hurry, other than the occasional brief take-off as mentioned above. With geese, a handler can keep up better than would be the case with sheep of a similar non-handler-oriented nature. When things go wrong, geese usually will quickly settle down again, but they provide more challenge than dog-broke sheep, the loose grouping of geese giving the dog more to do.

Different trialing programs treat geese a little differently. In the American Herding Breed Association, geese are considered separate from ducks and separate titles are given for them. In the American Kennel Club and Australian Shepherd Club of America programs, geese are considered to be the same as ducks as far as titles are concerned. Because geese don't like to be crowded into small spaces, the narrow confines of AKC's A course obstacles and the B course pen can be tricky at times. AHBA's arena courses provide some flexibility as to size of obstacles, and geese are especially suited for open-field courses and ranch courses, with the length of the course adapted appropriately.

If you get a chance, get to know geese. I really enjoy working them. It is a lovely sight to see a flock of geese gliding along in their stately fashion, supervised by a confident, smooth-working stockdog.

by Linda Rorem

(with thanks to Dot DeLisle and Joy Sebastian-Hall for their input)